Maternal Mental Health Week always causes me to pause and reflect on my experiences of mental illness, in the time before and after the arrival of my daughter.

I had some experience of mental health challenges in the years before I got pregnant, so when my midwife asked me at my booking appointment, I mentioned them to her. My partner and I knew that it was important that we knew where I could go for support if I needed it. My midwife was very supportive and reassuring. She referred me to the Perinatal Mental Health Team, and offered to check in with me regularly to see how things were going. At this time, that was all the support I needed. I was thrilled to be pregnant and although I had had a lot of early issues like bleeding, we were excited for what was to come.

I first realised that I was struggling at around 24 weeks. I began to feel very anxious about something happening to my baby, so much so that I felt unable to drive my car anymore, and I eventually stopped leaving the house altogether unless I had to. My midwife asked me how things were at one of my appointments, and I burst into tears. I felt so sure that she was not going to be able to find a heartbeat, or that something else would be wrong. When she’d found baby and all was okay, she talked to me about practical ways of coping through the next few months. She encouraged me to talk to my partner about my thoughts, and to continue to gently challenge myself to ‘do the scary things’. She also pointed me in the direction of organisations like PANDAS and the Samaritans, who I rang on occasions when things began to feel unbearable.

I felt like a weirdo for having the thoughts I did, and so I started to hide away from the ‘mum friends’ I had made during pregnancy. Whilst they were buying baby clothes and excitedly painting their nurseries, I was obsessively researching statistics on all the things that could go wrong in the third trimester. I began to feel absolutely certain that my baby would not come home with me. And, even worse, I started to feel sure that whatever went wrong would be my fault. I stopped being able to do any activities because they would trigger anxious thoughts about my baby’s wellbeing. I spent a lot of my third trimester hiding inside the house, cowering on my sofa, terrified for my baby.

The perinatal team were a great support during this time. I also found lots of support came from a few friends that I was able to confide in, and they helped support me by keeping in touch regularly, and accompanying me on trips out of the house. My midwife continued to check in with me regularly and reassure me that all was well with my little one. I also began to follow a few Instagram accounts that focused on maternal mental health, and the things they posted made me feel a lot less alone with the thoughts that were plaguing me.

Things unfortunately took a terrible turn when I had my baby. I experienced a traumatic birth, and my little one was very unwell. I spent many of the early days in a perpetual state of shock. I remember looking at myself in the mirror on the lift wall on my way down to NICU, poking my deflating stomach, and feeling as though that person was someone else. I didn’t sleep for days, sitting up in bed staring at the wall ahead of me. My head was so loud. Thoughts of how this was all my fault that she was poorly, how I didn’t deserve to be her mother, and how everyone must be judging me, swarmed around me. I began to think about ways to end my life, believing that my family would be better off without me.

Time passed by in a whir, an overwhelming blur of pain from my c-section healing, time on the Neonatal Ward and bone-chilling terror about my baby’s wellbeing. I instantly loved my daughter, and she felt like mine from the very start, but there was this unrelenting fear that that we wouldn’t be able to take her home, and that it was all my fault.

Eventually, she was well enough to come home with us. I tried to reassure myself that when we got home, things would feel easier. The terrifying suicidal thoughts I’d had in the immediate postpartum period had subsided, and I felt that being at home in our own space would be a relief. And it was… initially. We had a few days of lovely walks in the sunshine, family cuddles on the sofa, and everyone came to meet our little one which was great.

Things turned dark again when my partner returned to work. Suddenly, I was home alone with a tiny human for hours and hours at a time. Newborns are exhausting, but they also don’t do a lot, so I had lots of time whilst feeding or contact napping to be scrolling on my phone. I quickly became obsessed with doing the ‘right’ thing – googling and reading for hours and hours all the research about whatever area I was focusing on at that time. I was already sleep deprived looking after a newborn, but I would choose to stay awake even when she slept, believing that I could only keep her safe if I knew everything there was to know about how to be the ‘best’ parent. My daughter was medically vulnerable, and this fed my fear that I had to be perfect, or else something awful would happen to her. Whenever my daughter went back into hospital, I would cry next to her hospital cot, believing that the doctors would tell me any second that I was at fault and that they’d take her away from me.

Alongside this, I was having flashbacks that would explode out of nowhere. We would be playing on the playmat, or I’d be pushing the pram, and suddenly I would be right back in my birth trauma. I’d be assaulted with the smells of hospital, the sounds of hospital, I’d feel blood running down my legs when there was nothing there… even the walls of my house would become the colour of the hospital walls. It was absolutely terrifying, especially because they couldn’t always be predicted, and I was alone, and responsible for a tiny human!

I started attending some baby groups, and the company was helpful, but it felt hard to fit in. Many people wanted to share their positive birth stories with me, which was painful to hear, and seeing other people’s babies (and hearing parents talk about new things their babies had learned to do) fed my anxiety about my own daughter’s progress. Having a child with medical vulnerabilities and some developmental challenges made me feel like the odd one out and I often felt ashamed of talking about them, because I felt like my daughter’s challenges were my fault. Some brave mums talked about their own experiences of struggling to bond, losing their identity, and even feeling that they regretted having their babies. And whilst I admired their strength to share their feelings, I felt even more alone. I didn’t regret having my baby, I had bonded straight away, and I loved her more than anything, so why was everything feeling so unbearable?

The turning point for me is known as ‘the day of the spoons’ in my house! It was a day of many small things. It started with a horrible flashback whilst I was showering, that made me vomit and leap out of the shower soaking wet, running to my daughter to check she was still breathing. I took my baby to a group where somebody innocently asked me if she was rolling yet (she wasn’t) and I felt sure that they’d asked because they felt I was a rubbish mum, I wasn’t doing enough practising with her etc. When I got back in the car, I had a panic attack because I believed I would crash the car on the way home. I rang the Gloucestershire crisis team, who talked to me until I was calm enough to drive home safely. When I got home, I started to research the best spoon to buy to start weaning in a few weeks time. I became fixated on it, and long after my partner had come home and the baby had gone to bed, I was still googling. My husband told me that I had to turn off my phone and go to bed, but I couldn’t. I had to know what the ‘right’ spoon was. He took my phone off me and I became hysterical… and in that moment, we both realised that things were not okay and I needed more help.

When the morning came, I rang my Health Visitor. She arranged a time to come round to talk, and when she came, I told her all the dark thoughts and feelings I had been having. I burst into tears as I showed her the list on my phone of current anxieties I had about my baby – everything from worrying about her head shape to researching how likely it was that our roof would collapse in on her and kill her… my HV was incredibly kind and reassured me that I wasn’t well, and I needed support, but I was a good mum, and my daughter was okay.

From that moment onwards, things started to get better. I had support from the perinatal team, and I found PANDAS to be very supportive too. My GP was helpful in reassuring me about my daughter’s wellbeing, but also had some great tips for how to manage my health anxiety – for example, only allowing myself to look things up on the NHS website, and limiting my phone usage. I met with a psychiatrist and was diagnosed with PTSD and an anxiety disorder. She referred me for CBT, which provided me with some really helpful strategies for managing the cycle of anxious thoughts. Eventually, I was able to access EMDR therapy to process and heal from the birth trauma and my daughter’s hospital experiences. This was a slow and painful process, but ultimately helped me to find myself again, after many months of being buffeted back and forth in the storms of trauma and anxiety.

I started attending a group for mothers who were experiencing some postpartum mental health challenges, and this was an incredible support. I felt able to share with those mums how bad things had been, and as a group, we’d often talk about solutions and ways to help ourselves feel calmer and healthier. I slowly began to open up to my friends and family about how bad things had been, and therapy had helped me learn what I needed to ask for from them to support me – things like, treading carefully when discussing my daughter’s development, for example.

It was still a very challenging time. Support was not always that easy to come by, especially NHS services that could sometimes be overstretched and there were incredibly long waiting lists for therapy. I had to force myself to keep pushing for the support. I rang back when calls weren’t returned, and I made myself make contact with professionals like the Health Visitor if I needed to see them. I often felt like I didn’t deserve support, but when I considered not getting help, I looked at my daughter and reminded myself that she deserved to have a healthy and happy mummy. I found that resources like Instagram accounts, supportive groups and friends, and helplines were a lifeline when there were gaps in care elsewhere – there is a lot of scepticism about the toxic positivity in ‘go for a walk’, ‘have a cup of tea’ and other such suggestions, and they absolutely would not have cured my PTSD on their own… but the little moments of self care that I was able to manage, helped me make it through until appointments were available.

My daughter is now much older, and I am much healthier. EMDR therapy helped stop the flashbacks that used to consume me. I will probably always find it a bit emotional to think about my birth and how poorly my daughter was, but the emotions don’t overwhelm me anymore. Therapy helped me find strategies that I still use today, so although I’m still quite an anxious parent, I have ways to manage my thoughts now. I have used my experiences to give back, through volunteering and the job I do now, which has helped me find a sense of purpose in what happened to us.

Most importantly, though, I recognise that, even when things felt unbearable, I was (and am) a good mum. When I look back on photos from that time, I can see the terror in my eyes, but my daughter is happy, loved, and having fun. I wish I could go back in time and show myself then what I can see now – that perinatal mental illness had me in its grasp, but the support and love of people around me would get us through, and most importantly, the love for my daughter would overcome all.

My top tips for anyone who recognises themselves in the place that I was are these:

- Proactively seek support from professionals – your midwife, Health Visitor and GP. Make a noise, even when you’d rather hide away. In an ideal world, the systems would be easier and quicker and less busy, but until they are, keep asking for what you need.

- Find groups and friends who fill your bucket, not empty it. If a group isn’t feeling good, don’t return. Find ones that help you instead. There are mums out there who you can feel safe with, it might just take a while to find them. If real-life connection feels like too much, have a look at social media accounts or online groups. Remember that there are support lines that will listen to you, day and night.

- Prioritise self care. Waiting lists might be long, and even the gap between support can feel endless. Find some ways to soothe yourself in those times. It can be hard to find lots of time whilst looking after a baby, so find things that work for you. Some baby-friendly strategies that I used… walking outside, sitting in nature, dancing with baby, listening to audio books, doing ‘slow stitching’ whilst she napped (lots of examples on Instagram!).

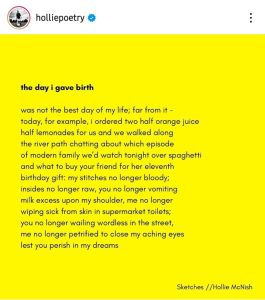

I wish you all well, this Maternal Mental Health Week, and in all the weeks when we don’t speak about our mental health as much as we should. There is much hope in this poem by Hollie McNish, the often unspoken recognition of how hard early motherhood can be, with a fierce grip on the hope of the many days of parenting to come. I hope, wherever you are in your parenting journey, that you can hold on to a little bit of that hope. x

Sources of mental health support can be found here.

Image description:

the day i gave birth

was not the best day of my life; far from it –

today, for example, I ordered two half orange juice

half lemonades for us and we walked along

the river path chatting about which episode

of modern family we’d watch tonight over spaghetti

and what to buy your friend for her eleventh

birthday gift; my stiches no longer bloody

insides no longer raw, you no longer vomiting

milk excess upon my shoulder, me no longer

wiping sick from skin in supermarket toilets;

you no longer wailing wordless in the street,

me no longer petrified to close my aching eyes

lest you perish in my dreams

Hollie McNish